Anodized Coloring Aluminum Plate for Construction

Most people meet anodized aluminum long before they realize what it is. It might be the satin finish on an office façade, the shimmering ceiling panels in an airport, or the warm champagne tone on a boutique storefront. Yet behind that familiar surface lies a surprisingly technical material: anodized coloring aluminum plate, engineered at the intersection of metallurgy, electrochemistry, and architecture.

A useful way to understand this material is to stop thinking of it as “painted metal” and start thinking of it as a controlled transformation of the metal’s own skin. The color is not just on the aluminum; in a very real sense, it becomes part of the aluminum.

The Surface as a Functional Interface

In construction, every exposed material is really an interface with the environment. For aluminum plate, this interface must manage rain, UV radiation, urban pollutants, salt spray, hand contact, and temperature swings, all while preserving appearance for decades. Paints and coatings sit on top of the metal as foreign layers; anodizing turns the uppermost aluminum into a coherent, crystalline oxide barrier.

Through anodizing, the natural oxide film on aluminum—normally just a few nanometers thick—is grown in a controlled way to microns in thickness. The result is an aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) layer that is:

- Harder than the underlying metal

- Chemically stable in most atmospheric conditions

- Transparent or translucent, able to host dyes and pigments

- Microporous in its unsealed state, allowing absorbance of color

Instead of asking, “What can I stick onto aluminum to make it look good?” the anodizing process asks, “How can I make the aluminum itself the finish?”

Alloy Choices: Designing the Substrate for the Finish

Not all aluminum is equal when it comes to anodized coloring plates. The alloy’s microstructure, impurity levels, and constituent elements strongly influence color uniformity, gloss, and corrosion resistance.

For architectural anodizing, several wrought alloy families are common:

1xxx series (commercially pure aluminum, such as 1050, 1100): excellent anodizing response, high reflectivity, but lower strength; often used where forming is critical and loads are modest.

3xxx series (manganese alloys like 3003): good formability with improved strength over pure aluminum; widely used for interior panels and lightly stressed exterior elements.

5xxx series (magnesium alloys such as 5005, 5052): the backbone of many façade systems; good corrosion resistance, especially in marine or polluted environments, and very suitable for anodizing when Mg content is controlled.

High-silicon or high-copper alloys, while strong, tend to produce dark, mottled, or uneven anodized finishes and are typically avoided for visible surfaces.

A typical chemical composition for an architectural-grade 5005-H34 anodizing plate might look like this:

| Element | Typical Range (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Si | ≤ 0.30 |

| Fe | ≤ 0.70 |

| Cu | ≤ 0.20 |

| Mn | ≤ 0.20 |

| Mg | 0.50 – 1.10 |

| Cr | ≤ 0.10 |

| Zn | ≤ 0.25 |

| Ti | ≤ 0.10 |

| Al | Balance |

The temper designation, such as H32, H34, or H36, indicates controlled cold working and partial annealing. For façade panels, these tempers are chosen to balance flatness, strength, and formability. Too soft, and the panels dent; too hard, and they crack during bending or form visually noticeable stress patterns under the anodic film.

From Raw Coil to Colored Skin: The Process as a Narrative

The manufacturing path of an anodized coloring aluminum plate can be read like a story, where each step writes a new chapter into the surface.

It begins with coil or sheet rolling. Here, surface defects are the villains: roll marks, inclusions, and scratches will be magnified, not hidden, by anodizing. Mill finish quality is therefore non-negotiable. Many producers specify special “anodizing quality” coils to ensure minimal streaking and inclusion content.

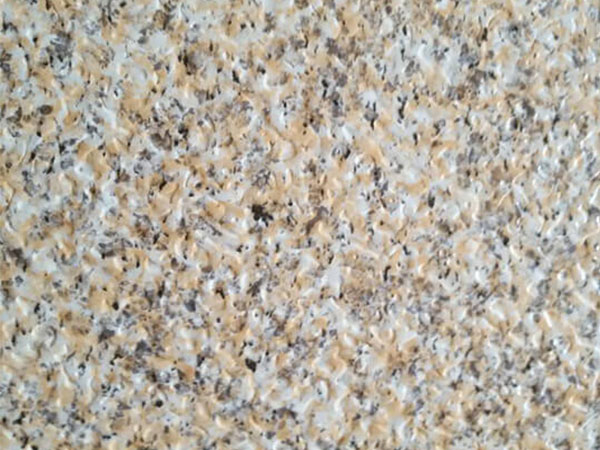

Next comes pre-treatment: degreasing, etching, and desmutting. In alkaline etching, the surface is gently dissolved, leveling micro-roughness and giving a uniform matte or satin appearance. The “style” of the final finish—high-gloss, satin, or matte—is partly defined here. Two coils of the same alloy can look entirely different after anodizing if they receive different pre-treatment regimes.

Only then does true anodizing begin. Immersed in an acid electrolyte (commonly sulfuric acid) and made the anode in an electrical circuit, the aluminum grows a controlled oxide layer. The process variables—current density, electrolyte temperature, time—determine the oxide thickness, typically in the range of about 5–25 μm for building applications.

At this point, the oxide layer is like a three-dimensional honeycomb of microscopic pores, standing on a dense barrier layer. Those pores are the gateway to color.

Coloring: Light, Depth, and Perception

Coloring anodized aluminum is not just about hue; it is about depth, light scattering, and angle-dependent appearance. That is why the same bronze or champagne shade can appear warm in morning light and almost steel-like under an overcast sky.

Several coloring approaches are common in construction:

Electrolytic two-step coloring

Organic dye coloring

Here, organic dyes are absorbed into the pores. This offers a broad palette, including vibrant reds, blues, and greens, more suited to interior applications or sheltered exterior zones due to potential UV fading over time.Integral coloring

The oxide film is colored during growth by modifying the anodizing electrolyte and conditions. This can produce very durable, subtle tones, though the process is more specialized and less widely used than two-step electrolytic coloring for large architectural programs.

The final act is sealing. Immersing the colored, porous oxide in hot deionized water or a nickel-based sealing solution hydrates and swells the oxide at the pore mouths, effectively closing them. Seal quality defines stain resistance, color retention, and corrosion behavior. Poor sealing leads to chalking, fingerprint susceptibility, and dye leaching.

Performance in the Built Environment

It is tempting to think of anodized coloring aluminum plate purely in aesthetic terms, but its value to construction is largely functional.

The anodic film sits at about 300–500 HV in microhardness, while many structural aluminum alloys are much softer. This hard, thin skin resists scratching better than most paint systems. Because the oxide is inorganic and tightly bonded, it will not peel, crack, or delaminate under UV, the way some polymeric coatings can over time.

Corrosion behavior is another quiet advantage. The anodized layer acts as a barrier against chloride ions and industrial pollutants. In coastal projects, anodized 5xxx alloys with proper thickness and sealing have a long history of service. The oxide layer is also electrically insulating, which can help mitigate galvanic effects in contact with dissimilar metals, when details are thoughtfully designed.

From a fire performance standpoint, anodized aluminum is essentially metal plus inorganic oxide: it contains no combustible organic binders and no halogenated flame retardants. In curtain wall and rainscreen assemblies, this contributes to meeting increasingly strict fire regulations.

Standards as the Invisible Contract

Behind every panel that looks “right” for decades is a web of standards that define expectations for quality and performance. While these vary by region, several reference points are typical in the industry:

- Anodic film thickness for exterior architectural applications is commonly specified around 15–25 μm, depending on exposure.

- Color difference across a façade zone may be controlled using ΔE tolerances measured against a master panel.

- Seal quality is often checked by dye stain or conductivity tests to ensure adequate pore closure.

International and regional standards, such as ISO 7599 for anodizing of aluminum and its alloys, or EN 12373 series and their successors, describe test methods, film classifications, and performance criteria. Architectural associations and façade system suppliers then build project-specific specifications on top of these frameworks.

The presence of these standards allows owners, architects, and contractors to treat anodized coloring aluminum plate not as a gamble, but as a predictable, verifiable system.

A Material That Ages Honestly

Perhaps the most distinctive quality of anodized coloring aluminum plate, viewed from a long-term architectural perspective, is that it tends to age honestly rather than theatrically. It can pick up a softer sheen over time, slight tonal shifts, or mild patina at water run-off zones. Yet it rarely fails in the dramatic, catastrophic ways that flaking coatings or corroding steels can.

This makes anodized aluminum a particularly appropriate material for buildings intended to live gracefully for decades: civic centers, transport hubs, universities, museums, and residential complexes that aim to look intentional rather than newly decorated.

In the end, anodized coloring aluminum plate is more than a decorative option. It is a carefully tuned system where alloy composition, temper, surface preparation, oxide growth, coloring, and sealing are all aligned to create a thin, invisible technology between architecture and atmosphere. The colors we see on the street are simply the visible trace of that alignment.

https://www.al-alloy.com/a/anodized-coloring-aluminum-plate-for-construction.html